Mechanisms and History of Manual Therapy: Part 1

Manual Therapy seems to be steeped in tradition, mystique, and various amounts of uncertainty. Especially for students and young clinicians who are occasionally intimidated by the prospect of using their hands to assess, diagnose, and treat people.

The aim of this blog series (2 parts) is to demystify manual therapy (MT); to look at the history, the research, and to explore an evidence based framework to guide how we reason through its use.

Leonardo Da Vinci

The Father of Medicine

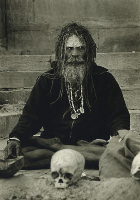

The history of MT explains some of the mystique. To begin with, manipulative therapy has been around since at least 360 BC. Early accounts involve ‘bone setters’ in Norway, Russia and Nepal. There’s evidence it was historically used in Japan, China, and India; the Balinese (of Indonesia), the Lomi-Lomi (of Hawaii), and the Shamans of Central Asia all used it.

In his book on joints, Hippocrates, the father of medicine, described traction and thrust pressures by way of levers to treat a ‘gibbus’ or prominent vertebrae. He even noted that this treatment should be followed up with exercise. What a guy! Roman surgeons (Galen), persian doctors (Avicenna), and Italian geniuses (Leonardo Da Vinci) all had a hand in crediting and passing along accounts of MT through the ages.

This puts us in the interesting company of both giants of medical history as well as with the Witch Doctors of the ages. Take heed. Not until the 19th Century, did manual therapy get formalized by the likes of Andrew Taylor Still (the founder of Osteopathy) and Daniel David Palmer (Chiropractic); who built up theories of how MT works based on human anatomy and biomechanics. Still’s theories were centered on the ‘disturbed artery’ hypothesis which posited that obstructed blood flow could lead to disease and pathology.

Daniel David Palmer: Founder of Chiropractic

Palmer contended that if a vertebrae was ‘out’ it would put pressure on the nerves which would go on to have an effect on the viscera. These theories, like many things, caught on by way of persistence and marketing. Palmer used the mass media of the day --radio -- to advertise his services and ideas. Pair these charismatic claims with the fact that the treatments would have had some degree of effectiveness, and it’s not hard to see a ready-to-go recipe for confirmation bias.

Andrew Taylor Still: Founder of Osteopathy

Florence Nightingale

Let’s tangent towards the origin story of PT. Florence Nightingale, the mother of Physical Therapy, was a ‘professional assessor’ trained in mathematics and statistics. She led a medical effort for British Soldiers in the Crimean war in the 1850s. She and her team of 38 nurses did their best to treat wounded soldiers; they used massage and remedial exercises as part of their treatment. At this stage there’s no mention of manipulative therapy. Nightingale went on to form a school for nurses. Her students would go on to found ‘The Society of Trained Masseuses’, which went on to become ‘The Chartered Society of Massage and Medical Gymnastics’, which went on to become ‘The Chartered Society for Physiotherapy’ in 1944.

During and after this advent of Physiotherapy, Edgar and James Cyriax, Mary McMillan, Michael MacConaill, Freddy Kaltenborn, Stanly Paris, Geoff Maitland, and others all took a hand at developing manual therapy and integrating it into the Physiotherapy profession.

With all these different voices there were unsurprisingly a number of competing ideas about how manual therapy works, and how one should go about applying it. Chief amongst these within the PT world, Maitland proposed a theory of tissue tension/reaction, which competed with Kaltenborn’s theory that arthrokinematics and osteokinematics should underpin how we go about using our hands.

“These theories grew into some impressively sophisticated systems over time, but despite their complexity and the allusion of science, it was all predicated on guesswork, not on anything empirical.”

The problem here is that everything was based on theory. There was a basic understanding of biomechanics and anatomy that paired with some nifty best-guess-work to become the foundational constructs under which MT was based. It’s important to emphasize that ideas like flexion/extension restrictions, subluxations, and Maitland’s signs & symptoms approach were all based on what these thought leaders came up with in their heads. These theories grew into some impressively sophisticated systems over time, but despite their complexity and the allusion of science, it was all predicated on guesswork, not on anything empirical.

None of them were right.

Joel Bialosky, a prolific researcher and manual therapy debunker, identifies these systems as enticing supple minds by way of offering “seductively plausible biomechanical theory” even when these theories have been, not just unproven, but patently refuted in the literature.

Goodbye everybody!

Stay tuned for the next blog which will review the literature on MT and land on an evidence based approach to reason through the who, when, where, and why of Manual Therapy.