Injury & Healing: Redefining Terms

By now you know that I am a big advocate of pain science in rehabilitation and strongly believe that it is the best way to engage in a biopsychosocial approach to treatment. However, a while ago I noticed that I was having a negative reaction to the words” injury” and “healing” when interacting with patients. Previously, I was quick to “correct” someone that pain does not mean damage, when they would describe an injury, to start using a pain science approach from the beginning. However, I began to realize that down-playing injury for a term like “sensitivity” may help some people, but it might also alienate others… such a strategy may not legitimize our clients experience, as well as under emphasize the body's natural ability to heal! To really connect with our patients, and build therapeutic alliance, we must speak their language.

This presented a problem for me as most patients describe injury, and desire healing; and yet I couldn’t connect with them on this primary level. And without connecting with my patients, I would be missing the boat on using a biopsychosocial approach to its fullest (great blogs on that topic here). So, what was I to do? Force everyone to see my point of view… not likely effective. Instead I had to re-define my terms of “injury” and “healing” to speak with my patients in their terms while at the same time find a way to present pain science concepts. While I fear this may be a self-indulgent blog, my hope is that it will help you build a robust therapeutic alliance with your patients, while integrating pain science concepts to address the “bio” and the “psychosocial” in your treatment.

Let’s define injury.

Webster’s dictionary defines injury as:

An act that damages or hurts : wrong

Violation of another's rights for which the law allows an action to recover damages.

Hurt, damage, or loss sustained” (ref)

The urban dictionary defines it as:

Damage done to a body part that results in it being broken.

Either way you slice it people most often associate injury with damage, pain, or being broken. To be able to connect with patients, these must be in our concept of injury. But pain science tells us that pain and damage are not the same thing. The best definition of pain is provided by the international association for the study or pain (IASP):

“Pain is an unpleasant sensory or emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.”

The key point here is that it is “actual OR potential tissue damage.” As such pain is an experience, or an output of the brain, based on inputs to the nervous system, experience and perceptions. As an example, pain levels have been shown to be modulated by expectancy of threat (i.e. greater pain was reported to cold-pressor task when the application of an inert hand cream was not paired with an analgesic expectation; ref). However, this analgesic expectation effect is nullified if participants had previous experience of pain during the experimental cold pressor task (ref). I would argue that pain could be thought of as a loss of nervous system resilience (see figure 1) resulting in a continued perception of threat by the nervous system to a stimulus.

In the same way tissue damage could be thought of as a loss of resilience (i.e. loss of the tissues structural integrity and thus function; see figure 2). In animal studies injury of a skeletal muscle is defined as a deficit in maximal force production, where for a given muscle fiber sarcomere length is not uniform after injury with the areas containing the longest sarcomeres showing the greatest damage (ref). Interestingly a recent BJSM narrative review on classification and grading of muscle injury in humans concluded, ”there is limited evidence to support either the pathological or prognostic validity of clinical and radiological grading systems” (ref). This observation suggests prognosis is not as simple as identifying the degree of damage to the muscle.

Figure 1

Figure 2. Loss of tissue Resilience, rather than tissue damage

Figure 3. Loss of confidence

Finally, I would also argue that our concept of injury should consider a loss of confidence of the individual, particularly in the movement and activities our patients love to do (see figure 3). As physiotherapists, this is likely where the psychosocial is so important! We can’t assume that altering someone’s pain, or restoring tissue resilience, will automatically give them the confidence to return to their desired activity!

Studies have shown a strong association between fear of re-injury, as well as fear avoidance beliefs and function and sport participation. Fear of re-injury (as measured by the TSK and FABQ) has been demonstrated to be related to decreased self-reported function during ADLs and Sport in those with recurrent ankle sprains or ankle giving way episodes (chronic ankle instability; ref). Additionally, fear of re-injury (measured by the TSK) was also associated with decreased knee quality of life and the inability to return to previous levels of activity after ACL reconstruction (ref). The goal of physiotherapy is to return patients to the movements and activities that are important in their life. A loss of confidence (i.e. a fear of re-injury and fear avoidance of movement) stands directly in the way of this goal.

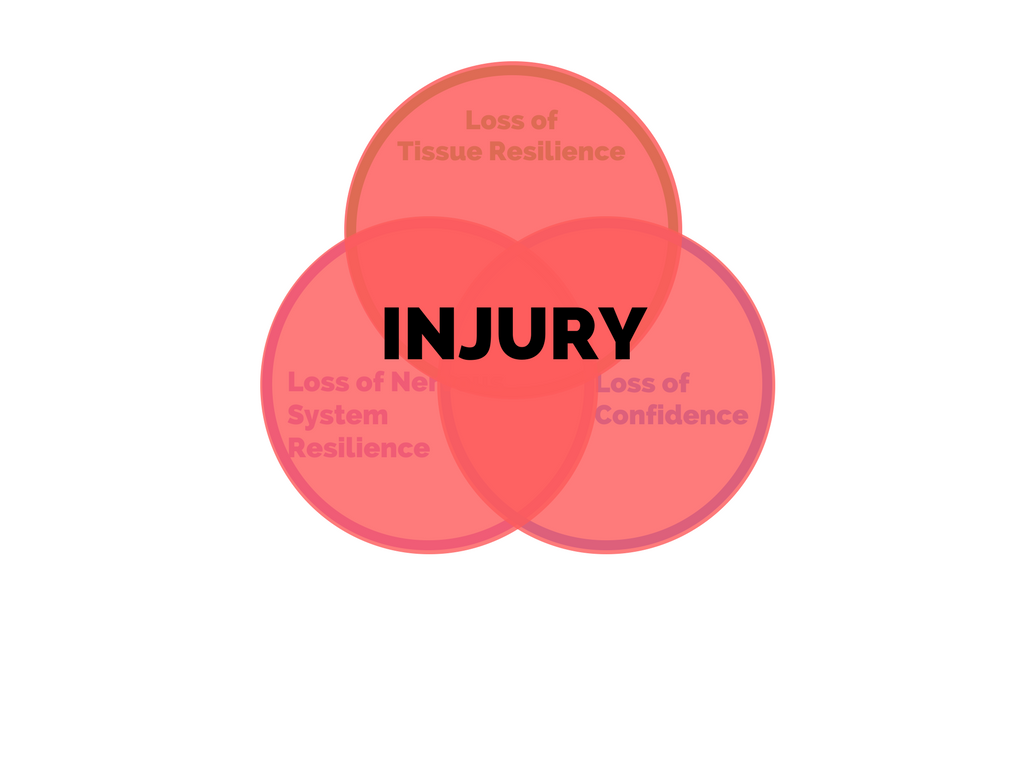

I am suggesting that we conceptualize “injury” as all aspects of lost resilience of the nervous system, MSK tissue, and confidence (see figure 4).

Figure 4. Conceptualizing “injury”

When a patient comes in and describes themselves as injured, we should consider that they could mean any one, or any combination, of these three domains. What we do as physiotherapists is to determine which domain is most contributing to the patients “injury” at that time, and to help guide them toward “healing.” The difficult part of our job is that this is a moving target… the main domain isn’t always the same from visit to visit.

But what is “healing” then? I would suggest thinking of it as the corollary to this definition of “injury.” “Healing” is the intersection of restoring tissue resilience, nervous system resilience, and confidence (see figure 5). Here is the great thing about this concept of “healing;” all our interventions fit neatly inside of it. Restoring tissue resilience… time and exercise do this! Restoring nervous system resilience (i.e. decreasing perceived threat)… manual therapy, education, and exercise do this! Restoring confidence… education and exercise do this! The art of what we do comes down to the timing and dosing of these interventions.

Figure 5. Conceptualization of “healing”

The most powerful thing that I see physiotherapists do is to remove our patients’ barrier(s) to movement and enable them to return confident and happy to the activities they love! To be successful at this we must be listening and watching our patients with the same intention we had on their first visit, every visit. We are granted the opportunity to help our patients achieve their goals everyday we go to work. This is the biggest gift our profession provides to each of us, patient and therapist a like!

Educate. Encourage. Empower.

CURTIS TAIT, BSC, MPT, IMS